by Huỳnh Công Nam Sơn ’25

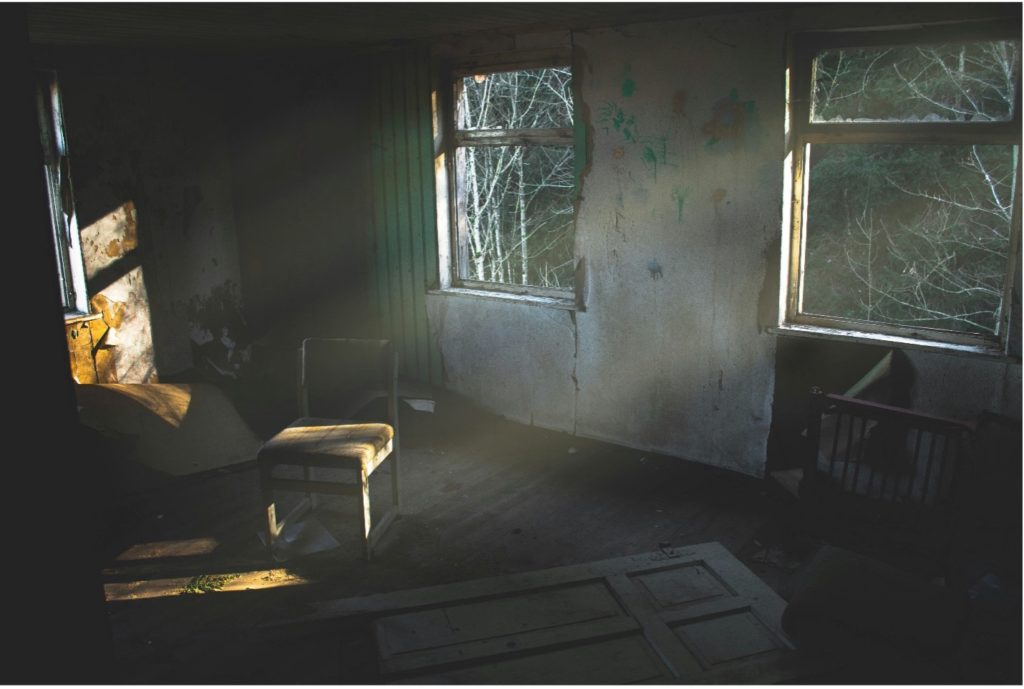

“If you can’t even clean your own room, who are you to give advice to the world?” asked Jordan Peterson six years ago on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast. We all remember the memes of how persuasive Peterson was compared to our mother in getting us to start vacuuming, for instance. At the opposite extreme, among those of us who took the statement too seriously in the metaphorical direction, there was the philosophy of room cleaning: A person ought first to get their personal affairs in order and cultivate for themselves an orderly mindset before they may go out and change the world.

This sounds fine as a principle. Still, sometimes it is not within our control that our “room” is a mess—if this metaphorical manner of speaking be pursued. Sometimes, our own “messes” are the making of an externality, such as a less-than-ideal familial relationship or a subject at school that we do not excel at immediately. These take time to resolve themselves. We leave our “room” all the same to perform our functions in society.

Has a third and more useful interpretation of Peterson’s imperative here suggested itself? In toeing the line between the literal and the metaphorical, ought we to seek another mode of thought which concerns psychological order by its analogy to the physical practice of cleaning our room? To do this, we slightly shift hereafter the sense of the process from “cleaning” to “organizing” to talk about its relation to the mind without falling into incoherence. The question is thus articulated as follows:

Is organizing your room in any way similar to organizing your thoughts?

Not at all—you may say. Objects in our room neither spontaneously multiply themselves into existence nor forcefully eliminate each other by means of contradiction, unless one happens to live inside Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons. To organize objects, one need but have a minimal vision of where everything ought to belong: what goes in the bin, what needs repositioning.

By contrast, our thoughts elude immediate discernment, sometimes up until the moment of articulation. As wrote E. M. Forster, allegedly, “How can I tell what I think till I see what I say?” This is the gravest difficulty for us as budding writers in an academic setting. Regardless of our experience with the context behind a writing assignment and knowledge of its chief expectation, our thinking begins as an inarticulate blob of cognitive biases, unfounded sentiments, and self-contradictions, all ever so slightly married by a vague sense of common purpose. To speak of organizing thoughts at this stage is to partake in nonsense, for one has yet to possess them.

But is this initial assessment too pessimistic? Give pause to our confidence and revisit how we have sketched the process of organizing our room. It has been said by way of example that the acts involved include discarding and relocating items—yet this too is an unfortunate suggestion of the blobby sort. In accepting it without question, we have contented ourselves with the illusion of insight, forgoing the necessary reflection which may yet betray it.

For the sake of brevity, I shall state here what I take to be the case. We discard items from our room which are no longer of use or interest for the sake of relevance. We shift things around to bring out coherence by way of proximity. We sweep the floor and add new things in order to preserve and enhance beauty. These three characters—relevance, coherence, beauty—bring out in writing a virtue of purposiveness, akin to that which Allen Edgar Poe calls the single effect. They are the adhesive that gives sustained thinking a certain wholeness, as well as the very possibility that the value of this whole may be elevated above the sum of its parts.

This, too, may be challenged. The appearance of plausibility is mortal—and so are we. The provisional nature of a conclusion ought not to deter us from inducting it into our practices, leaving behind quietism for another day. This is the presupposition behind all scientific and philosophic thinking. Still, my hope is that I have provided you with the traction needed to continue on your own in contemplating the analogy proposed. The next time you find yourself in need of thinking and writing, it may yet serve you well to pick up the broom.